Hindsight has been kind to Alfonso Cuaron’s Children of Men. At the time the film didn’t break any box office records, but it was lauded for its eerily prescient take on what society might look like on the brink of collapse. Never flashy or over the top, it was a classy, understated achievement. Only now is its influence apparent.

Set in London in 2027, after a global flu pandemic and years of human infertility, journalist Theo Faron (played by Clive Owen in a career best role) is contacted by his ex-wife, Julian, to aid her and her group of radicals smuggle a woman named Kee to the coast. He enlists help from his government-appointed cousin Nigel (who has largely disconnected his feelings from the world), and his old friend Jasper, a retired political cartoonist caring for his paralyzed wife.

Very odd, what happens in a world without children’s voices.

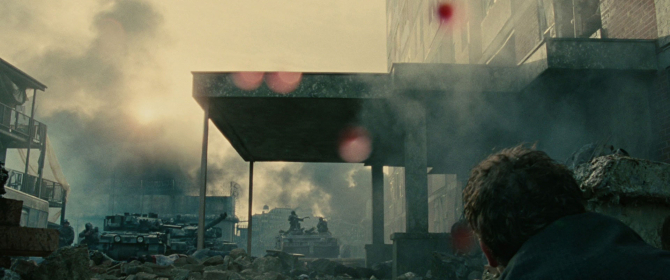

It’s a essentially a chase movie in structure, as Theo and Kee run from their pursuers, stumbling into the crossfire of an almighty battle to regain control of an immigration camp on the way. It’s a desperately human struggle, with lives hung on to by a thread. Very tense stuff.

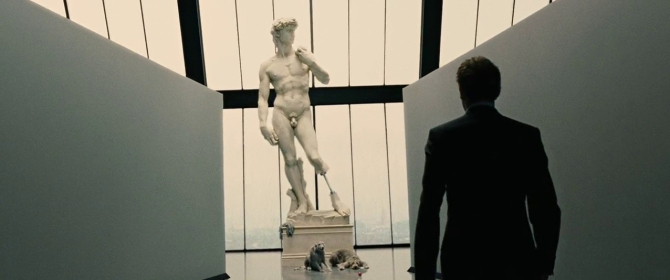

The backdrop to all this is important. We see the final moments of a society burdened by challenges it cannot cope with. Overwhelming migration, political unrest, disease pandemics, terrorism.

These all looked fairly sci-fi ten years ago, but are numbingly regular occurrences today, leaving us with entire countries lurching towards the right in response. It’s food for thought, and Children of Men doesn’t paint a very rosy picture of how we deal with such big issues.

Visually, Children of Men ushered in a new set of tools that hadn’t been deployed like this before. The now famous unbroken shot of the attack on Julian’s car was so novel, people didn’t notice how impossible it was the first time they saw it. The big battle inside (and outside) the abandoned building at the end is also a high watermark. As with the rest of the film, it’s not designed to call attention to itself, more to put you inside the scene. It does that brilliantly.

Oddly, a scene that sticks with me is one that doesn’t often get talked about; Theo escaping from the farmhouse at dawn. It’s done in such a way that you can totally put yourself in his shoes. It’s minimal. There’s no music score. Barely any sound at all. It plays out in what feels like real time. The threat is life and death, and it all comes down to whether he can walk on gravel lightly, and open a car door without noise. The shot of him rolling the car down the hill, silently, with a group chasing on foot is so real and so tense it’s almost unbearable, and the relief when he escapes is palpable.

From the first blast of chaos in the opening scene, to the ambiguous ending filled with hope and uncertainty, Children of Men is a mature attempt to look at humanity’s future. It’s freaky that it turned out to be such an accurate one in some respects, but all good sci-fi hits the bullseye, whether it be good or bad (think of HG Wells predicting mass evacuations of British cities 50 years before it happened).

It’s a bleak film, but there’s beauty here too. Beauty in the truth of sorrow, survival, grief and hope. For me, one of the best movies of the 2000s.

Leave a Reply